History of the Canal

History of the Canal

The canal was initially proposed by merchants and coal miners in Leeds who wanted a link to the Irish Sea and the thriving continental trade of Liverpool's world famous port.

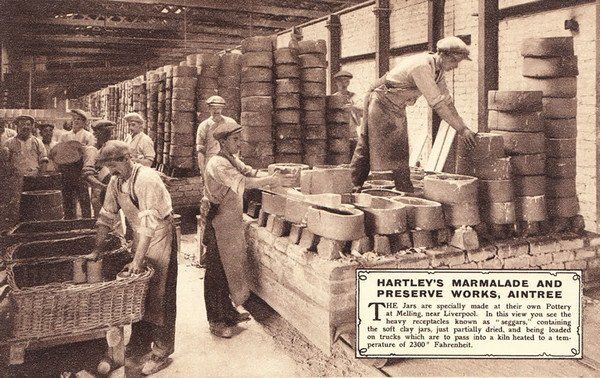

The canal strengthened industry within Liverpool and the surrounding area, allowing for much greater development of trade. The original Tate & Lyle factory was birthed out of the trade in sugar on the canal, whilst the first Hartley's jam factory was born out of Aintree, relying on the sale of sugar on the canal to start their business.

Many other materials and goods were transported along the canal, including limestone, coal....and manure, referred to as 'night soil' (due to it being collected from neighborhoods after twelve), along with all other general refuse of communities, was transported away from living areas along the canal to be used by surrounding farmers.

No matter how many barges travelled along the Leeds and Liverpool Canal the surface remained the same, flat and smooth. It’s been like that for 200 years.

Conversely the towpath did wear out; horses straining to pull heavy barges, loaded with coal or cobble stones or grain or sand or cement, made sure of that! Heavy hooves pounding down, day after day, can wear away the hardest surface. Even cobblestones within the towpath wore down and were regularly replaced so that hooves could hold their grip.

Two hundred years ago, without horsepower, canal barges could go nowhere. Only horses on well maintained towpaths could pull heavy cargoes all the way from Liverpool to Leeds. Horses were the pulling force which made the canal viable. Horses doing heavy work have to be fed, groomed and given rest and shelter. They need to be loved. A farrier was always on call to replace buckled, worn down, iron shoes.

At the top of Hall Lane in Maghull, near to the swing bridge, stables were built to house horses, barns to store grain, and a large area of land was laid aside to store materials. This facility was essential for the upkeep and repair of what became a vital lifeline for the transport of goods throughout the land. Timber, coal, sand, salt, cement, bricks, gravel, cobble stones, rocks, pitch, paint, paintbrushes, pickaxes, spades, sledgehammers, nails, screws, iron bars, steel sections, tackle and fodder for horses, horseshoes and many more things ,too numerous to mention, were held to cover any requirement for the smooth running of the canal. Nearby stood the ‘Travellers Rest’ an inn where tired workmen could rest and seek refreshment.

A canal bus ride, from Liverpool to Wigan, was available on some barges for a penny. Space was made amongst cargoes of coal to accommodate about four passengers at a time. The journey took best part of a day.

During very cold winters the canal froze over and icebreakers were brought into use to keep the canal operational. The method used was simple and effective...Barges, shaped like Viking ships with pointed bows, were pulled along by horses, while up to six men jumped up and down, holding on to a crossbar running the length of the vessel. A combination of snorting nostrils and clogdancing kept the waterway clear.

At intervals along the canal’s length, men were employed, solely to store and maintain these special vessels. The depot at Maghull was charged to provide icebreaking duties all the way to Litherland, in one direction and to Halsall in the other.

Icebreaking was such an exciting operation it made everyone passing nearby stop and stare. Adults, on their way to work and children, on their way to school in Melling and other villages along the route, stood mesmerised as the parade passed by.

Towards Liverpool, near Brewery Lane, barges discharged their payloads into a large yard and an ever growing mountain of coal became visible for miles.

The coal was mined in Lancashire and distributed, far and wide, from the yard by horse and cart. This kept houses warm and factories busy.

Men and young children, and ponies, worked miles underground to bring coal to the surface. It was then shovelled manually into barges and heaved struggling by horses to reach its destination.

Hard work, in miserable conditions for little pay, day after day, was all there was to look forward to 200 years ago but the building of the canal heralded the start of better working conditions for many.

Today, hard work on the canal has been replaced with the provision of pleasure cruises for all, but a canal bus trip to Wigan still takes best part of a day.

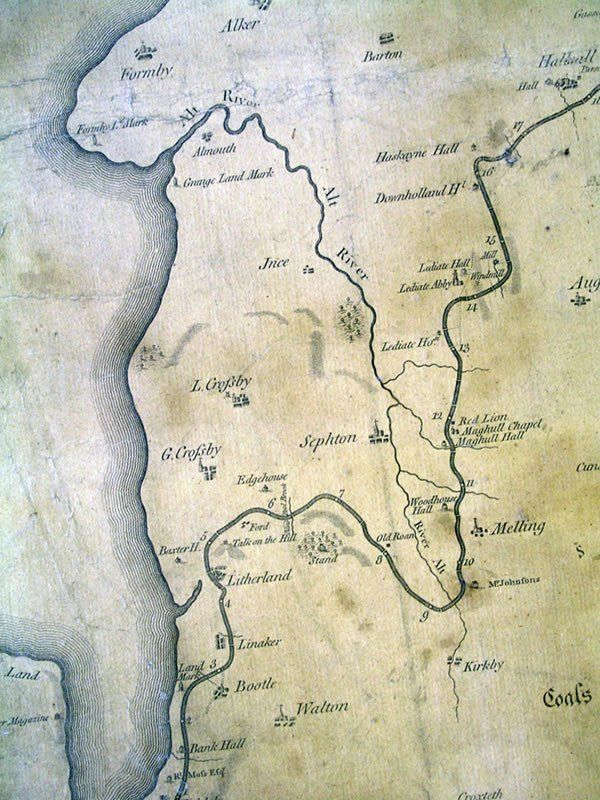

Map from 1770 before the canal was constructed

The Melling stretch of the canal was opened in 1774, click here to see maps, (make this a link to the maps) and ever since Melling and its community through time have had a close relationship with the canal. From the farmland and families to the industry, they all relied on the canal for their existence.

Holmes swing/turn bridge

Melling had its own pottery industry situated adjacent to Pye’s Bridge (now known as Ledson’s Bridge, next to the Horse and Jockey pub, itself replaced in the late 20th century) on the east side of the canal. The pottery was opened as The Midland Potter in 1872 by John McIntyre and William Murray of the Caledonian Pottery, Rutherglen, Glasgow. It was sold to John Turner, the pottery manager in 1889 and bought by Hartley's the jam maker in 1922. Stone jars were made here and taken along the canal to Hartleys Jam Works at Aintree and Scottish potters came to Melling to work. Unfortunately the pottery works was badly destroyed by fire in 1929 and never reopened again.

Unloading Clay, Melling Pottery

Melling Pottery

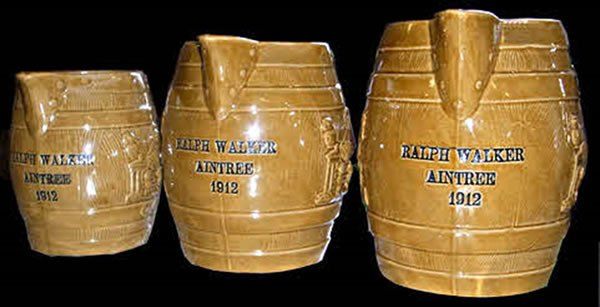

Jugs made at Melling Pottery

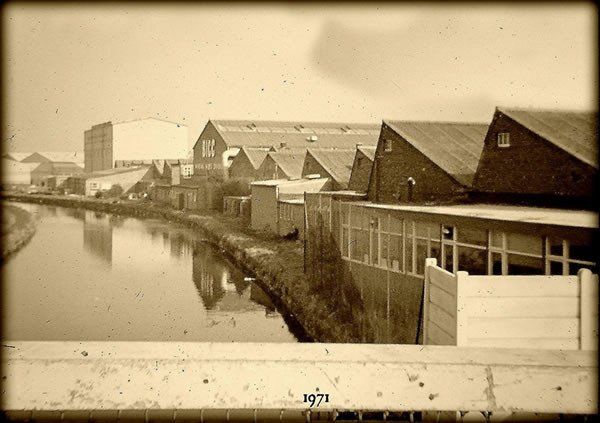

Bicc Factory 1971

Village Estate (former site of BICC factory)

Clayton’s Bridge (now known as Melling Stone Bridge)

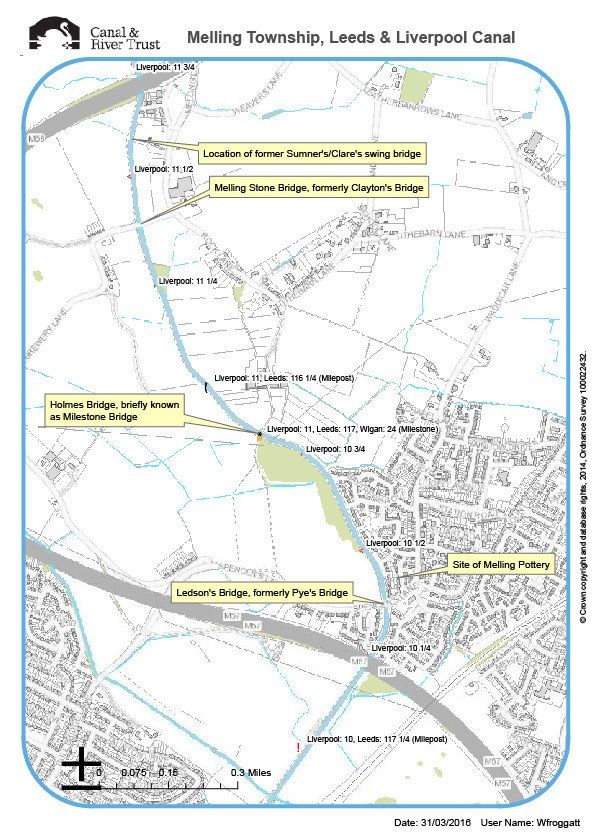

The Melling township map above shows the locations of the mileposts/milestones, or at least where they should be if they still existed. Originally the canal was marked with milestones (made of stone); there was one on this section adjacent to Holmes Bridge. Very few of these remain. They were superseded by the mileposts with which we are familiar with today (made of iron) in the mid 1890’s. The map shows milestones as an orange triangle. The mileposts are represented by red/black dots: big dots mark the mile, small dots the quarter mile, half dots mark the half mile. Black dots represent mileposts that still exist; red dots represent posts that no longer exist. Note the position of the milestones and mileposts don’t correspond.

In 2016 the Leeds-Liverpool Canal celebrated its Bicentenary year, and local villages and towns along the historic stretch of waterway came together to mark this momentous occasion with a programme of events. Melling celebrated with a fantastic community day which incorporated a fun canal fact find, a delicious family bbq, outstanding entertainment by local community groups and an impressive 30 boat flotilla of narrow boats and motor boats cruising along the canal, all beautifully decorated in bright bunting and occupants dressed in traditional boating clothing.

For our younger canal explorers you can find lots of fun canal activities, such as a “Waterside Bingo” and “Habitats challenge”, on the Canal and Rivers Trust Explorers website. https://canalrivertrust.org.uk/explorers/resources

For bigger explorers there is lot of really interesting information about the canal on the Sefton Canal website. http://seftonscanal.webplus.net